Ann Herbert Scott is a distinguished writer of books for young children. An award-winning author, her work has been published in Spanish, French, and Eskimo, as well, of course, as in English. Ann Herbert Scott is a distinguished writer of books for young children. An award-winning author, her work has been published in Spanish, French, and Eskimo, as well, of course, as in English.

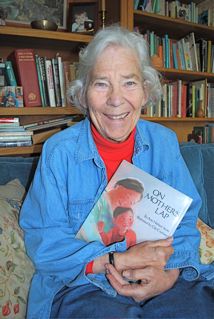

Scott was born in Philadelphia on November 19, 1926, the beloved only child of newspaper editor Henry Laux Herbert and singer and artist Gladys Howe Herbert. She grew up in a close family with two great-aunts and one great-uncle sharing an old farm house in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. From early days she was interested in writing, social concerns, and the life of the Spirit. These interests have remained with her through the years and continue to be central to her now that she is in her eighties. Scott received a rigorous formal education, first at Springside School and George School, later at the University of Pennsylvania where she majored in English, and at Yale University, where she received a master’s degree in social ethics. Later she took classes in social work at the New York and the Connecticut Schools of Social Work. Later still she sat in on history and psychology seminars at Oxford University and a series of art and print-making classes at the University of Nevada. Scott’s interest in writing for young children grew out of experience as coordinator for Wider City Parish, a pioneering interracial group ministry working in low-income housing projects. In the Elm Haven Housing Project she found it difficult – actually impossible – to find books about children of color, interesting books in which her children could see themselves. In the fifties almost no such books were being written. If I ever have time, Scott told herself, I’m going to try to write a book that would hold the interest of Franky Brookshire (a particularly bouncy four-year old who could never sit still for a story). “At last I found the time to write,” Scott remembers, “when I married William Taussig Scott, a theoretical physicist who was moving to Nevada to help develop a graduate physics program at the University. “There I set to work on the bibliography of a scholarly book my husband was writing but in my spare time I began puzzling about my story. The manuscript began to take shape when I remembered a small boy in a cowboy outfit sitting alone by a window near his Elm Haven apartment. There he was: Big Cowboy Western! Now all he needed was a horse. I remember vividly the night I was doing the dishes and I thought of the old Italian produce man who visited the project each week with his horse and wagon. My plot was complete.” Several weeks later on a warm May Saturday morning Scott’s husband took his scholarly manuscript to the post office and Scott, who had never even read a book on children’s literature, sat down in the backyard with her old L. C. Smith portable typewriter and wrote the manuscript of BIG COWBOY WESTERN, her first book. There is a lot of luck in publishing and Ann’s came three months later when she met Marguerita Rudolph, an early childhood expert and writer of books for young children. Ann got up her courage, showed Marguerita the manuscript, and was thrilled to hear Marguerita say, “Why this is a book and I know just the editor to send it to.” Two weeks later came a letter from Jim Giblin, then a young associate editor at Lothrop, Lee and Shepard, offering Ann a contract. Lothrop was so quick in response because suddenly the publishing world had come to realize that there were millions of children left out of their books and editors were looking for manuscripts like Scott’s. Upon publication BIG COWBOY WESTERN was welcomed warmly. “We need more books like this one,” School Library Journal commented with a starred review. Next came LET’S CATCH A MONSTER, a followup of the adventures of little Martin of BIG COWBOY WESTERN. There might have been a series about Martin and his friends and family but the work was interrupted by the tragic death of Richard Lewis, the gifted young illustrator of COWBOY. Meanwhile an entirely different book was taking shape. In another stroke of luck Scott visited Aileen Fisher in her home in Sunshine Canyon, Colorado. This veteran children’s writer advised Scott to “get another string” for her bow. “My editor thinks writing picture books is difficult,” Fisher explained, “but it really isn’t fair to publish more than one a year. Look into nonfiction, or plays or poetry.” Scott looked into nonfiction. A fascinating job as an enumerator in the 1964 Census of Agriculture led to the discovery that no one had written a book about the United States Census. How to explain the reasons behind the questions on the complicated forms? What was their history and their function in our present society? A letter to the Public Relations Office of the Bureau of the Census confirmed that the Bureau of the Census would welcome a popular book on its work. At the Bureau Scott met with an enthusiastic group of specialists. She commented to her husband that the Census staff reminded her of a group of physicists, men (and they were at that time all men) working in their shirt sleeves and not paying attention as to who had a Ph.D. and who had not. Most important these experts were delighted to find someone who believed their work was interesting and they shared their knowledge with gusto. The census book was a several year project involving two prolonged visits to Bureau headquarters in Surtland, Maryland, other related trips to census operations in Ohio and Los Angeles, and a part-time residency in the government publications department of the University of Nevada library. Of the multitude of interesting experiences the highpoint was an evening in National Archives where she held in her hands the actual homemade forms of the census takers of 1790. After some complications of publishers and delays relating to the arrival of son Peter, CENSUS USA, Fact Finding for the American People 1790-1970 was published by the Seabury Press in 1968. Although it was listed as “Young Adult,” statisticians, economists, sociologists and political scientists found it of interest. Eminent statistician Dr. Stuart A. Rice wrote that the book brings into view “the moist grass roots of a subject usually regarded as very dry and dreary,” stating that “to an exceptional degree for a subject of this kind, her story combines human interest, sound historical narration, and the exposition in simple language of subjects usually discussed by freakish people called statisticians.” One of the challenges to Scott was writing a book that would be accessible to both young adults and to experts in the field. Approval came from several sources: the selection of the book as a Book of the Month alternative, appreciative reviews in professional journals, and the news that scholarly Dr. Conrad Taueaber had held up the book with high praise at a major Conference of Population and Housing Census Users. The briefest comment came from Scott’s Aunt Agnes who declared her, “the best writer in the family.” During the long period of involvement in the world of the Census, other projects were brewing. During those years part of the rhythm of Ann’s life was teaching First Day School (Quaker for Sunday School) to a gaggle of little pre-schoolers. When the time for juice and cookies arrived, Ann found herself repeating, “No, just one.” Ann soon was in the small child’s world: not just one cookie, not just one balloon, not just one ride on the merry-go-round. What could be available in limitless supply? Of course, it is love. The book fell into place easily and Ann mailed it to Jim Giblin with considerable confidence. Jim immediately replied with a phone call. The manuscript had arrived and he announced, “It made my day.” Soon Scott discovered the complexities of children’s publishing. NOT JUST ONE did not make the day of the senior editor (Jim was still a somewhat junior associate) and the manuscript was rejected. It was sometime later that Scott received another call from Giblin: “Do you still have that manuscript? Good. I’m editor-in-chief now and I want to publish it.” From the start the work on NOT JUST ONE was a model of the smooth and continuous interaction of writer, artist and editor Jim Giblin at Lothrop who consulted Scott from beginning to end. Lothrop contracted with artist Yaroslava Mills to do the illustrations and sent copies of the dummy and cover art for Scott’s input. Yaroslava captured the heart of the book and Scott was delighted with the final version. It was then that she discovered the central importance of the artist in the creation of a memorable picture book. Meanwhile work was progressing on a little slip of a manuscript called SAM. The manuscript was a direct gift from a child. Scott often referred to it as her “instant book” as it developed with no pre-meditation. It all began with a visit from Scott’s young neighbor, an energetic inquisitive boy named Mark. When Mark twirled the dials of the washing machine and set into motion the load of wash destined for the dryer, Scott told him it was time for him to go home. An hour later, as she was scrubbing out the bath tub, the idea came to her:: an active, inquisitive little boy going from one member of the family to another seeking attention and each time being pushed aside because everyone was too busy to play with him. Scott first visualized the book in terms of her New Mexico friends the Marchettis with their eight energetic children but she soon realized, for simplicity, the size of the family should be reduced to two siblings, a brother and sister. Then Scott went to her office and in a few minutes typed out the manuscript of SAM. The conception of SAM may have been instant but its process of proceeding to publication was not. First of all Jim Giblin turned it down at Lothrop. Convinced it was a book Scott turned for advice to her old mentor Marguerita Rudolph, and Marguerita in turn took the manuscript to McGraw-Hill who were publishing children’s books at the time. Editor Eleanor Nichols wrote immediately that she would like to publish the book and that she had a “very distinguished” artist in mind, but she asked Scott if she “would mind” having the story set in a “Negro” (that was the word then) family. Scott was delighted to welcome a distinguished illustrator turning her family into a family of color. She was also pleased at the mention of a seven hundred and fifty dollar advance, just the sum the Scotts had due on their income tax. The contract was duly signed and the illustrator was named: Symeon Shimin whose art Scott had long admired. The work on the book proceeded but there was no contact with Scott until she received in the mail an advance copy of the book’s jacket. The editor was enthusiastic but Scott was shocked. The portrait of the soulful brown boy on the cover bore no resemblance to the bouncy preschooler Scott had envisioned. And to Scott’s horror the covers were already printed! What to do? It was too late for Scott to have any impact, she had not even met Editor Eleanor Nichols, who had already proudly shown the cover to an important meeting of librarians. Scott concluded she had best remain silent. Scott heard that the artwork was running late. But evidently Shimin often ran late. The seriousness of the delay became apparent when a huge package of photocopies of the art work arrived – via airmail special delivery with the request that Scott return the photocopies by airmail special delivery the following day. Scott opened the packet with trembling anticipation. Here were end papers of the same soulful child followed by page after page of magnificent portraits of the little boy – this other little boy – and his family. Scott was up all night, reading and rereading the manuscript. It did not really matter whether or not she liked the illustrations, what mattered was whether or not they contradicted the story. After a sleepless night, Scott wrote Eleanor Nichols that the little boy of her story, the bouncy youngster who goes from one family member to another with a series of merciless putdowns, was not the sad-eyed boy of the art work and, in fact, the sensitive child of the illustrations would never be treated that way by a loving family. Then followed a long period without communication. Scott feared McGraw-Hill might be abandoning the book. Then came a new illustration of a little boy playing with an upside down chair and the project was saved. The book came out late, too late to be considered for the Caldecott Medal, but it was named a “Notable Book” by the American Library Association and heralded as a classic. None of the critics noticed the discrepancy between the story and some of the artwork. Although Scott’s work was receiving attention, including a much-publicized reading of SAM by Ethel Kennedy on the first year of Sesame Street, she herself was not writing. The arrival of baby Katie and the move of the whole family to Oxford University for Bill’s sabbatical year took priority over anything else. There was only one exception, again the gift of a child. And this time her own child. One sunny morning Katie was peaceably sleeping in her crib and two-and-a-half year old Peter was snuggling in Ann’s lap. One by one Peter brought his favorite toys: his stuffed puppy, his plastic train and his Nutshell Library books. Ann’s lap was full. Suddenly baby Katie cried. Ann brought Katie from her crib and all three cuddled down in the big chair. Fortunately that story was not lost in the business of the morning. Almost immediately Katie’s baby sitter arrived and Scott drove Peter to his play group. Scott was then free for a few hours. Clinging to her story idea she drove her little English Ford up to a market parking lot and on a yellow legal pad on the cramped front seat of the car Scott wrote the draft of ON MOTHER’S LAP. By the time it came to pick up Peter she had finished her shopping and was on the way home, clutching the pad with the beginning of her book. For some months the manuscript went untouched as Ann was busy being a faculty wife with two small children. When she finally got back to the book she changed the easy chair to the rocking chair the family had in Reno and added the rhythmic refrain: “Back and forth she rocked.” The book was complete. Scott owed Lothrop a manuscript so she sent the story off to the new editor there (Jim Giblin had moved on from Lothrop by then). The editor promptly returned the manuscript with an appreciative letter, affirming the work but stating it would depend on the illustrations and she did not have the right artist at the time. So Scott put the manuscript back on the shelf. Moving back to Reno after a year in England and Italy and caring for two small children took all of Scott’s time. It was then that she gave up her office to become Katie’s bedroom, a loss that affected her work for many years to come. At that time Scott received and rejected two offers from an encyclopedia editor and an adult non-fiction editor to take on work about the Census (she had inadvertently become the most expert freelance writer in the country on the subject of census-taking). However, Scott gave her priority to her family, thus cutting off a promising career as a writer of adult non-fiction. Again Scott consulted Marguerita Rudolph for her opinion as to whether ON MOTHER’S LAP was a book. And again Marguerita took the manuscript to Eleanor Nichols at McGraw-Hill. Nichols immediately offered a contract but with the stipulation that the illustrations be provided by Glo Coalson, a young artist who had just come into the office fresh from six months in Eskimo country in Alaska. Nichols was delighted with her suggestion but Scott was appalled. She always wrote about what she knew and she had never even been to Alaska, let alone known an Eskimo family. To make matters worse Scott had conceived ON MOTHER’S LAP as a book for small children, for children as young as one year old but old enough to have a tiny baby in the family. Adding the dimension of Eskimo life seemed to complicate the utterly simple story. Every book is an individual and most books seem to have their own problems. Scott had hers with the Alaska Eskimos. Nichols assured her that Coalson had spent six months in Eskimo Country. Scott replied that she had spent years in Paiute Indian Country and despite numerous friendships there she did not feel ready to do a Paiute story. Glo Coalson sent Scott a striking water color of a solemn Eskimo woman whose severity, Scott felt, did not go with the warm, motherly feeling of the mother in the manuscript. Finally Scott read the manuscript over the phone to an Eskimo ethnographer with the American Indian Historical Society who pronounced that his brother lived in Nome and that an urban Eskimo story would be welcome. Furthermore he promised to give his expert attention to each illustration and to every word of the text before the book was ready for publication. The book finally came together with beautiful heartfelt illustrations by Coalson. It was reviewed as a universal story and none of the critics seemed to notice that the illustrator and not the author had the authentic experience necessary to create an Eskimo book. ON MOTHER’S LAP was published in 1972 and there was a seventeen-year gap before Scott’s next book. The intervening years were busy but often frustrating, the story of many women of that day. Every morning Ann watched her husband Bill set off on his bicycle for work. At the University of Nevada he had two offices, a research assistant, and a secretary who typed his every word on her spiffy IBM Selectrix typewriter. At home he had in Ann a careful editor and proofreader. In retrospect Scott realized she should have used her royalties to provide a day or two a week for professional work. Now she smiles in regret that she did not have the self-confidence to assert herself in those empty years. However, in many ways the years were not empty. Scott was able to be a stay-at-home mother who was usually ready with milk and cookies when her children came home from school. She was also an energetic Quaker and activist for peace and justice concerns (about which we will hear later). By now Katie was growing up, an unhappy adolescent in urban Reno who hated school and didn’t want to look for a job. Finally one day her exasperated mother told her, “If there is anything you want to do, I’ll help you do it.” “Mom,” said Katie, “I want to live on a ranch with dogs and horses.” With the help of a Nevada social worker the Scotts found Sharon and Mike Badger, kindly Elko County ranchers with a kennel full of Golden Retrievers and family connections with the Big Ranch, thousands of sagebrush acres outside of Mountain City, near the Idaho border. It was a happy fit from the beginning and soon the Scott’s adolescent daughter was riding free. When Ann first met the Badgers, and Mike discovered she was a children’s writer, he immediately told her of Sharon’s Uncle Frank, an old buckaroo who was full of “big windies.” At the first possible opportunity Ann drove ninety miles to Mountain City to meet the fabled “Unc.” The old cowboy was as lively as his reputation and he and Ann hit it off from the beginning. Suddenly a door was opening to a new chapter in Scott’s life. A grant from the Nevada Council for the Arts made it possible for Ann to interview a number of old buckaroos. She spoke to these old cowboys wherever they would talk to her, not only in family ranches, but in small cabins and bungalows and in a room in a buckaroo barn. She interviewed at a kitchen table, in the front seat of a jeep, on a sleigh winter-feeding cattle in a snowstorm, in an old log barn at four in the morning waiting for a calf to be born, by the side of the corrals during roundups and branding, near the stove of a comfortable living room where she battled to be heard over the loud TV. Hesitant to use a camera and impose distance, she relied on a pen and yellow pad to capture the memories. She talked with ranchers who had once been cowboys and to their wives and children. The grant ran out but Scott continued the three hundred and ninety mile trips to talk with Unc in Mountain City. She was looking for the sense of the Nevada buckaroo’s life, not in any kind of abstraction but what you might call the “furniture of the mind.” When a cowboy rolls out of his bedroll on a cold morning what does he feel and see? What covers protect him from the snow? Where is his war bag and what’s inside? What will he be eating for breakfast? It seems difficult to imagine anyone less suited to the buckaroo project than Ann Scott. As she described her experience to a Reno audience she declared herself, “a city dweller all my life, over aged, overweight, under-educated in the world of ranching,” and not even a horse woman. But the years of quiet observation paid off in writing which the reviewer of the New York Times declared “amazingly accurate.” Four books emerged from Cowboy Country, three from Elko County and one from New Mexico. The first Elko County book was SOMEDAY RIDER, the story of young Kenny who loves to go down to the corral to watch his father and the other cowboys bridle and saddle their horses. When he sees them ride off into the far hills, he wishes he were going with them. “Someday you will,” his mother tells him. “I’m tired of somedays,” Kenny answers. “I don’t want to be a someday rider. I want to ride right now.” Undaunted Kenny tries to ride Mrs. Goose, then Amelia the sheep, then a baby calf, but one by one they each toss him off. Eventually his mother takes pity on her son and teaches him to ride. Jim Giblin, then editor at Clarion Books, contracted with gifted Arizona artist Ron Himler to do the illustrations and Scott could not have been more pleased. What followed was Giblin and Scott having a dialogue between East and West. How old should Kenny be? Giblin thought seven or eight but Scott observed young riders at a junior rodeo where a three-year old girl sped by at full gallup. In country where it was not unusual for a parent to hold a diapered baby before him in the saddle it was no stretch of the imagination for a five-year old child to ride. In the end ALA Booklist greeted the book appreciatively, “With warmth and humor, this thoughtful story reflects a ranch kid’s unspoiled pleasures and true-to-life ambitions.” Four years later Booklist slashed the prospects of A BRAND IS FOREVER with its sensitivity to the vulnerability of librarians to probable animal rights critics. The book is the story of Annie and her beloved calf Doodle and the trauma of branding day. Despite Scott’s careful text and Ron Himler’s handsome illustrations, and despite the most appreciative New York Times review Scott ever received on all her western work, A BRAND IS FOREVER went quickly out of print. This was Scott’s first experience of the effect of a negative review from a highly regarded journal. It was also Scott’s first experience with Dinah Stevenson, the new editor at Clarion who advised Scott to turn her picture book manuscript into a chapter book with an unfortunate result of A BRAND IS FOREVER being shelved separately from Scott’s picture books and being often overlooked. In the midst of the Elko County stories Scott wrote a little counting book called ONE GOOD HORSE. Based on her friend Jimmy Marchetti’s taking one of his boys in the saddle to count the cattle on his New Mexico ranch, the manuscript came quickly, too quickly Scott realized later. On a yellow pad in the front seat of a librarian friend’s car, Scott used the trip from Los Angeles to Carson City to write the little story. ”One good horse, two buckaroos, three cowdogs,” and so on. The manuscript came so easily that Scott sent it off to Greenwillow Books without delay. It was only later, as Scott explained to school children, that she realized that with a little more work she could have changed the stagnant image of “eight clumps of sagebrush” to the more lively “eight jumping jackrabbits.” So “go over your manuscript many times before submitting it for publication,” Scott came to advise beginning children’s writers. Greenwillow told Scott that Lynn Sweat, a very experienced artist, would be the illustrator. No changes were made in the manuscript until one frantic phone call from a junior editor at Greenwillow declaring that the book would be demolished by critics unless she changed the subtitle “Cowboy” to something less sexist. Fortunately Scott remembered New Mexicans talking about “cowpunchers” and the crisis was solved. There was a different kind of crisis for Scott although none of the reviewers caught the problem. Not only did the sagebrush look like lettuce but the handsome mountain quail were shown as Eastern quail. Sweat lived in Connecticut and Scott assumed he thought all quail looked the same. Eastern reviewers didn’t know, but Western book sellers did. As with SAM, Scott wished she could have seen the dummy of the book and caught the mistake. During these years Scott was visiting with Frank Baker whenever she could. But he was an old man now, “all stove up,” as the cowboys say. The years of hard riding were taking their toll. Sometimes Ann would make the long three hundred and ninety mile drive to Mountain City to find Unc snoozing in his chair, too tired to talk. Her great break came when Frank was visiting his sister, Scott’s friend Della, and a blizzard set in. Della invited Ann to stay at her place and while the blizzard raged outside, the sister and brother shared memories and Scott tape recorded them. At last Scott felt ready to write about Unc and his life. The occasion of the composition was a memorable one. Ann was in Elko for the annual Cowboy Poetry gathering. After it was over she checked into a Motel Six where, equipped with orange juice, granola and a hot chocolate mix, she used her typewriter to compose COWBOY COUNTRY. Ann had arranged to be away from Reno for a week, freedom that was rare, and there at the Motel Six, she wrote whenever she pleased. Up till three o’clock at night, down for a few hours, then back to work for four days straight. The only break she took was a steak dinner one evening at a Cattleman’s restaurant. In the end she emerged with a finished manuscript. The new work felt like a long verse poem and she called Dinah with her excitement from a pay phone in the parking lot. Envisioning a small book of poetry Scott realized critics would have to take her work seriously, a change from the reviews which concentrated on the art work and usually referred to her writing as “simple, understated text.” This book, Scott imagined, might have no pictures at all, or perhaps a few black and white sketches at most. Editor Dinah Stevenson, however, had entirely different ideas. If the manuscript should be published at all, it would need to be a picture book and it must be cut in half. To Scott the cutting seemed an impossibility. This story of a young boy’s introduction to cowboy life was so full of buckaroo history and lore that she felt there were no words she wanted to cut. She told Dinah she would think it over and see what she could do. In the end, after several months, Scott cut the manuscript to Dinah’s specifications. Next came the question of art work. Scott, who had heard many cowboys laugh at mistakes in books about their life and gear, wanted a strong Western artist who knew horses. But again Ann did not have her way. When Dinah called to announce that Ted Lewin would do the illustrations, Ann’s question was, “Where is Ted Lewin from?” “Brooklyn,” Dinah answered. Ann suppressed a groan. “But does he know horses?” Ann queried. “I really don’t know,” Dinah replied casually, “but he and his wife are going to come out.” With Ann’s limited knowledge of the children’s book field, she did not know Lewin’s work. As soon as she hung up the phone, she rushed down to the Reno children’s library. There she found Lewin’s latest book, the story of a young Egyptian water carrier and his donkey. Looking at the illustrations of the donkey she sighed in relief. Lewin knew animals. The book was safe. Ted Lewin worked on a busy schedule and it was some years before Ted and his wife Betsy arrived in Elko ready to do the artwork for the book. By then Unc was dead (Ann had been able to read the manuscript to him in a nursing home before he died), and his younger brother Ted and his nephew Brett had reluctantly agreed to pose for the book. Ann met the Lewins in her little camper and the three of them set off for eight days in an experience of what a picture book can be when artist and writer are free to work together. Ted was the director of the production. He had studied the manuscript thoroughly and knew just what scenes he wanted to capture. Both he and Betsy were covered with cameras and ready to take literally thousands of photographs. Even though Ann and the Lewins had never met before they went back country in the cramped camper to Devil’s Canyon and beyond. There had been a crisis in the project that was solved by Scott’s friends the Mannings on the Owyhee Indian Reservation. Ted needed to get pictures of buckaroos rounding up cattle but spring had come early that year and all the Anglo ranchers had finished their work. Only the Western Shoshone ranchers were still herding cattle and the Manning family and their friends provided the necessary images. Due to their hospitality, all the cowboys depicted in the illustrations are Western Shoshone Indians. By end of the trip Ted was so enthusiastic about the material that he went back to New York hoping he could get Dinah to give him some extra pages for the book. Dinah agreed and provided Scott the space to add a new paragraph about the Indians of the region “who made their way on foot, gathered the wild seeds, fished the streams for trout, and trapped jackrabbits in the nets they wove.” Ted worked fast. Soon the photocopies of the dummy arrived in Reno from New York and Scott was stunned by their beauty. As for accuracy, cowboy poet Waddie Mitchell asked only half in jest, “What ranch was Lewin raised on?” Production went off without a hitch and the Lewins and Scott were left with a beautiful book and a lasting friendship. Several years later the Owyhee Reservation again became the setting for another of Scott’s books. This was another story that was directly inspired by a child, this time, little Badugwiche, who was confronted by an everyday challenge to his courage: his fear of standing up before an audience as part of his school’s spelling bee. In BRAVE AS A MOUNTAIN LION, the book depicts young Spider looking for wisdom to his father with his painting of a mountain lion, to his grandmother with her advice to be clever as a coyote, and to the spider in the carport who teaches him to be silent. The boy Spider follows all this advice and despite his fear comes in second in the spelling bee. The book ends with the congratulations of his whole family.“You did it!” his mother said proudly. “You stood right up there in front of everybody.”

“Brave,” said his father, “brave as a mountain lion.” For the art work Dinah Stevenson chose Glo Coalson who by then had illustrated a four-color edition of ON MOTHER’S LAP. Highly successful Coalson came from Texas and she and Ann traveled in the old camper to the Reservation. There Glo worked in a very different way from Ted. She quietly observed life in the Manning family, made a few pencil sketches and became friends with Badugwiche and his little sister. Her artwork was very different from the illustrations of ON MOTHER’S LAP but it was widely praised as showing a new image of Reservation life. BRAVE AS A MOUNTAIN LION sold moderately well in individual copies; however three educational publishers bought subsidiary rights and copies of the book are reaching millions of school children. Scott was immensely pleased that her realistic story could serve as a counter image to some of the violent pictures of Reservation life today. In a break in the Western work, Scott’s GRANDMOTHER’S CHAIR came directly out of her own family experience. Ann had a little rush-seated black and gold chair that had once belonged to her mother, then to herself as a little girl, then to each of her children in turn, and finally to her grand-children. With the aid of the big leather family album the grandmother of the story shows the photographs of her own history and explains how each child in the family enjoyed the experience of listening to her daddy’s stories and watching the stars at night. Scott dedicated the book to “the little black and gold chair, all who have sat in it and who will sit in it.” Jim Giblin, now editor at Clarion Books, found a young first-time illustrator and GRANDMOTHER’S CHAIR was published in 1990 without complications. It was a forgettable book. HI, Scott’s shortest and simplest manuscript, was published in 1994 after years of sitting in offices where the editors waited for “just the right” artist to come along. In the end it was Glo Coalson who Editor Patti Gauch at Philomel chose to provide the illustrations. The story of HI was yet another gift from a child, this time a little girl and her mother waiting in line in the University of Nevada post office. The child was just big enough to wave and say “Hi” to each new patron, but everybody else was too pre-occupied to say hello to her. Ann watched as the little girl’s voice faded and her enthusiasm dulled, until finally Ann was near enough to say “Hi” in return. Editor Patti Gauch at Philomel Books recognized the child in the manuscript and it was she who thought of Scott’s old friend Glo Coalson as the perfect artist for the book. Coalson reported that she had said “Hi” to “about a thousand children” in her home city of Dallas. She then converted her experience into a robust picture book filled with delicious pictures. In contrast to GRANDMOTHER’S CHAIR this was a truly un-forgettable volume and the American Library Association recognized it as a “Notable Book.” Scott later read HI to many children and to her surprise the book’s interest level was much higher than she had first imagined. Evidently standing in a long line and being overlooked is a common experience for small children and even the older ones remember how it felt. The combination of a text that speaks simply and directly to a child’s emotions and beautiful evocative illustrations of the text make Scott’s books memorable. It’s Scott’s experience that even the strongest text is lost without good illustrations. These days illustrations must be excellent to catch a buyer’s eye. During Scott’s career, she has been very fortunate to work with some superb illustrators. She observed that many books with weak texts are now sold for their appealing illustrations. But for a book to endure, both text and illustrations must be of high quality. Scott wants to write enduring books. At best she dwells in a story, pursuing every detail of the setting. If the territory is unfamiliar, as in the cowboy books, she is willing to spend years in getting acquainted. She appreciates artists and editors who have the same exacting taste. In general, Scott works over material for some time, usually simplifying and re-simplifying, often cutting out favorite phrases because they are not necessary to the thrust of the story. When there is something she is unsure about, for example a six-year-old child’s ideas about monsters, she will go directly to children to find the answer. She does a lot of talking and listening with children. Otherwise she works from memory and imagination. Scott says, “I always see picture books as I write them; the sense of the graphics helps shape the development of the manuscript. As a writer who specializes in picture books for young children, Scott’s work has peculiar aesthetic concerns. Although she is not an artist, she continually works with images in mind, leaving much of the telling to the skill of the illustrator. Her manuscripts sometimes go through twenty to thirty revisions. Scott’s reputation as a children’s writer is based on books which evoke universal themes: the security of a mother’s love, the yearning to be big and important, the courage to deal with fear. She is a realist, trying to fully depict life as she observes it, and she usually chooses to explore important matters of the heart within the framework of everyday scenes from the lives of young children. Scott has been a teacher, social worker, and administrator, but whatever career she has been involved in, writing and children have been part of it. Scott says, “I believe the pull towards children’s writing comes from something childlike in me. I’ve always enjoyed being around little children, and wherever we lived – farm, city, housing development – there have been a few small children who have been among my closest friends. The sense of delight and wonder little children bring to the here and now seems to awaken something deep in me. In contrast to writing for adults, which is often demanding for me, writing for children is often fun; usually it is full of surprises, springing up unexpectedly in familiar places with the same spontaneous independence as forgotten daffodils in a leaf-covered bed.” Now that she is living in a retirement community Scott is forced to rely on her memory of those spontaneous children who have helped form her life. In her career, Ann Herbert Scott is a co-founder of the Children’s Literature Group and a member of the Nevada Writers Hall of Fame. She directed “All the Colors of the Race,” a Nevada Humanities Committee conference on Ethnic Children’s Literature. Her own books have been in the forefront of depicting children of color. She is a member of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, the Author’s Guild, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and Phi Beta Kappa. Ann is not just a children’s writer; she is a writer who is trying in everything she does to make the world a better, more peaceful, and more loving place. |